People who live in isolated villages, surrounded by the forest, are almost invisible. If we do not create a legal framework to support them, their future does not exist. That's why the concept of “forest-dependent community” must be included into the new Forestry Code, which is now being drafted. To help them, first we must find out who they are and where they live. Now we don't know.

The 25-year-old SUV rumbles and screeches as it goes through the river ford and climbs a boulder-strewn dirt road, bordered by a ravine. „Come oon!”, Paganini shouts to the car and connects the 4×4. We have to drive the 7 km up to the top, to Stănila, in the Ivănețu mountains in Buzău county. „Nea Mitu used to live here, Nea Ion here,” he says and points towards a part of the forest which looks as if man has never entered there before.

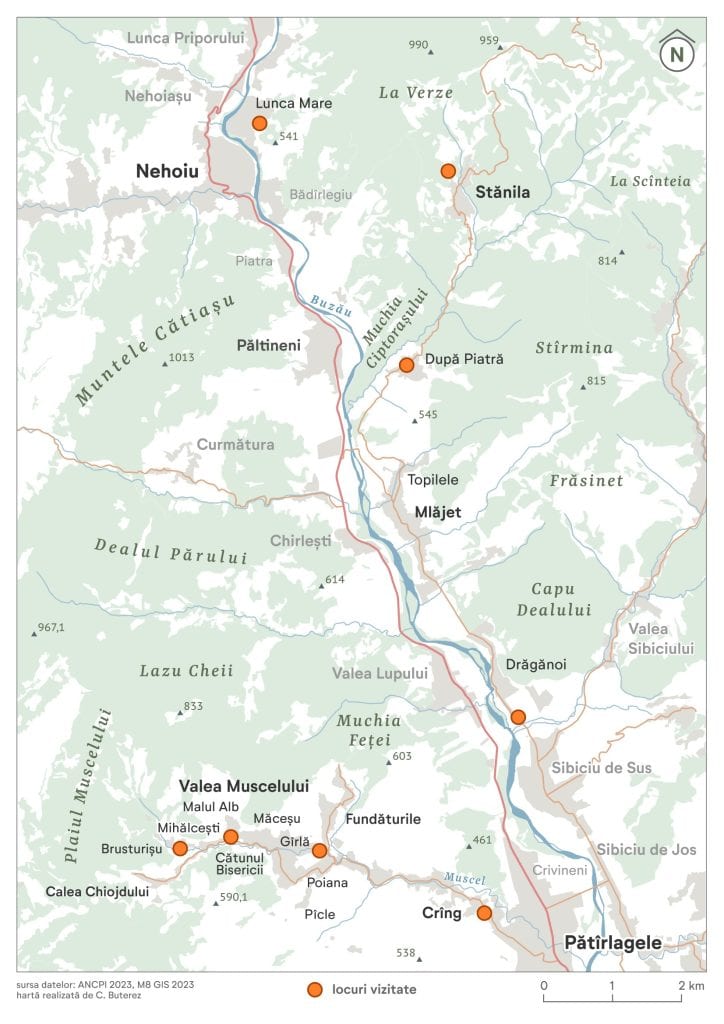

The road goes through the village of După Piatră, which does not even exist on the map. That is because there are more Romanian villages in reality than on paper, explains geographer Cezar Buterez, who studies the area intensively and maps it. The law merged them and they were administratively erased between 1950 and 1968, to make it look as if there was more population living in the cities than in the countryside. In reality, however, the locals still use the old names. For example, nearby there is Valea Muscelului, which includes 8 villages that are not recognized administratively and that do not appear on the map.

Paganini, 62, nicknamed like this because he has been a wood craftsman all his life and carves violins, was born here, up in the mountains, in Stănila. To go to school, he used to leave at 6 am, together with other children. They would cut the road short on a path, through the forest, to make it on time to school at 8 am. Out of more than 100 houses, only 6 are now permanently occupied. There are no kids left, the school was closed in ’74.

Stănila is the largest village in this endangered area. It is so vast that some of its regions have separate names. The car wheel almost slips into the gorge. Officially, we entered the village, but we are in the middle of the forest, no sign of people. „Over here we had the village stables, 80 heads. My grandfather had a blacksmith shop there, until the ’90s. Here the mayor lived, there was Nuță, the village boyar and, a little uphill, my mother's sister and my father's brother”, explains Paganini while pointing to different areas of the forest, on the side of the road, where nature has fully restored.

People who depend on the forest

It takes about an hour to cover the 7 km from Nehoiu up to Stănila. That's if you're lucky and it doesn’t rain, otherwise the road becomes inaccessible.

People who live in such isolated villages are self-sufficient and depend, almost always, on the resources provided by the forest such as wood, mushrooms, raspberries or plants. Unfortunately, until recently, the concept of forest-dependent community did not exist in the Romanian legislation. In fact, we don’t currently know exactly neither where they are, nor how many there are. Because we have no criteria to designate them and no procedures to identify them. Many times, when a law states that an area is strictly protected, entire villages, dependent in one way or another on working with wood, can find themselves overnight deprived of access to forest resources. Access which their inhabitants consider a fundamental right and without which these communities risk disappearing. That is why the new Forestry Code should be able to guarantee to these communities the access to the resources they depend on.

“I take the wood from the forest. If they turn this place into a Nature 2000 Site and tell me that I am no longer allowed to harvest the timber, how can I pay to cover my personal needs? Just as they forced me to pay taxes for the forest, they must give us the possibility, from harvesting this land, to earn enough to continue paying the taxes,” says Paganini, who inherited some hectares of forest from his father.

Wood Craftsmen

The road gets worse. After a steep turn uphill, a windowless building, overgrown with weeds, appears. It's the old school. We immediately arrive in the village center, at the now out-of-order Cultural Home, where one can still see the foundation stone laid by the villagers, on which is engraved: „Documentary stone founded in 1950 by the inhabitants of the village of Stănila”. It was a promise for a better life. It's semi-dark inside and smells like an old, decayed building. In a corner, on the floor, lies an old red mailbox, full of dust. „This is where I bought cigarettes from and this is where the tape recorder was placed,” recalls Paganini.

A little further up is his parents' house, where he grew up and where he comes every weekend. He carefully opens the traditional wooden gate, above which he wants to hang a large violin, carved in wood. „I grew up in sawdust, I felt the smell of my father’s freshly processed wood,” he recalls.

As a carpenter, he has worked with wood all his life. Starting a few years ago, he spends hours in his workshop near Nehoiu, where he sculpts violins. It’s a trade he learned from his father. „A violin is made of two wood essences: the face is of resonance spruce and the rest of curly maple, which is very rare,” says Paganini. To choose that piece of spruce from which to build the violin, he hits the already cut trunk, deposited somewhere near the forest or in a warehouse, with a hammer. Then he listens to its sound. When he hears the “FA diez major” sound, then he knows it is good. The maple must be selected directly from the forest, when it is still standing.

There are less and less traditional wood craftsmen, unfortunately, although their work is essential to preserve the cultural identity of some ethnographic areas. The elder ones didn’t usually have apprentices because the communist regime did not allow them to own workshops. And the young learn where they can.

A few villages away, Ciprian carves a new “troiță” (wooden cross). At 39, he has been sculpting for two decades. He learned to carve in wood by himself, without working with a craftsman. He spends time on both singing at the church and on sculpting troițe. “I realized I have created a trend. I was advantaged by the fact that I understand religious motifs and know how to put them on wood. People who have previously worked at the timber factory in Nehoiu have also started to carve troițe,” he says.

He works by himself, as he cannot afford to hire apprentices. In addition to the hours spent at the church, he also tries to do beekeeping. “To grow, I need a bigger machine, to finish my pieces. I would also need a bigger space, to have room for a team”. He can't afford to bid for timber harvesting in the forest, so the wood he uses is either offered to him by customers, or he takes it from sawmills or cantons.

There is no clear policy, at country level, to support such traditional craftsmen. „There should be local initiatives where they can participate with what they know. In addition, one cannot find them because there is no community to support and promote them,” says Buterez.

Up there, far away, feels good

We have crossed almost the entire village and still haven’t found the villagers. One must know where to look for them. The road gets rougher and steeper until it turns into a path. Paganini stops the car and enters the forest. There, in a house made mainly of wood, surrounded by flowers, live Mr. Florin and his wife, Verginia. He was a foreman and she was a dressmaker. When retired, they moved up to Stănila, where she had inherited a plot of land. They built their own house, have a vegetable garden, raspberries and a dog.

„It's good up here. We used to live in Nehoiu before, in a block of flats. However, the infrastructure is a real problem, there is no road to our house”, he says. So they bought a small tractor with a trailer, to carry their necessities. However, its engine got broken and, for three weeks, they had to walk the 7 km and carry everything with their backpacks. Mrs. Verginia brings us coffee. And dandelion syrup, which she had just made. And raspberry jam, from their backyard.

“These people should be encouraged to stay. I know many students who would like to return, but it is very difficult for them to start a business because those communities, which used to help each other, have disappeared. This is the real problem”, says Buterez.

It's almost evening, so we have to go down to the city. It's quiet in the village. It smells like hay, the noise is that of birds chirping. And, every now and then, of a dog barking. This is the present of the Romanian village. Hopefully, not their future.